|

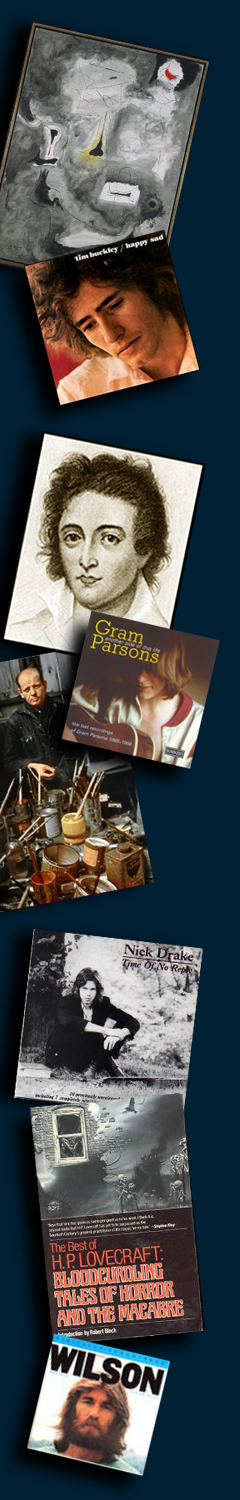

Her room was nothing like I had imagined. I guess

I had in my mind that she lived in a crypt or a coffin, a

dungeon or a cave, something spare and black and dark. It

wasn’t that at all. It was more like a guy’s room. There was

stuff everywhere. There were piles of books, biographies on

Ambrose Bierce

and Houdini, art books of the works of Jackson Pollock

and Ray Johnson, fiction by Kate

Chopin, David Hartwell, Robert Bloch, and a ragged copy

of Gray’s Anatomy set off by itself. There were books of poetry

--

Shelley, Hart

Crane, Frank

O’Hara, Frank Stanford, Federico Garcia Lorca, and Sylvia Plath -- and a stack of nonfiction I didn’t

even comprehend, titles like The Psychology of a Rumor, Alan Turing: The

Enigma, Secret Signals, and stuff by Albert Camus. I had seen some of these books before, in my brother’s

room after he had started college. “What kind of grades do

you get?” I blurted out. She laughed. “Straight D’s.” At least

I had that on her. I’d been on the honor roll every semester

so far.

I also noticed that there was a paperback copy

of the Lovecraft

book she had grabbed when we first talked in the library.

It was on her bed, open with the front and back of the book

exposed. “Why did you bother to take that out of the library?”

I said.

She looked at the book and blushed slightly. “I

can’t keep any of this stuff straight. I need to get organized

better. Do you want to start on that for me?”

I looked around and saw that it was a hopeless

case. There were discs everywhere, and even vinyl.

Music by Tim Buckley, Nick Drake, Gram Parsons, Buddy Holly,

Patsy

Cline, Bix

Beiderbecke, Chet Baker, Robert Johnson, Mozart. (I

don’t know if these were the exact objects on that first visit,

but they were definitely things strewn around her room during

the time we spent together.) There must have been twenty or

thirty discs poorly stacked on the floor, and more than fifty

records spread around like a dropped deck of cards. About

the only thing I recognized was a Nirvana disc, everything

else was obscure to me, country and jazz and classical. There

were posters and postcards covering the walls, mostly of people

I’d never heard of, like Isadora

Duncan and Robert Schumann and a scarred, engaging, mysterious

man named Louis Kahn, or people I’d heard of but never knew

what they looked like, like Anne

Sexton and Amelia Earhart, but whoever they were, they were

everywhere, their dead faces plastered on the walls and their

eyes calmly watching me. Houdini was bound in chains in a large picture above

her computer, Natalie Wood smiled from Anna’s closet door, and James Dean stood

on a frozen farm pond above her bed, looking at his reflection

in the ice.

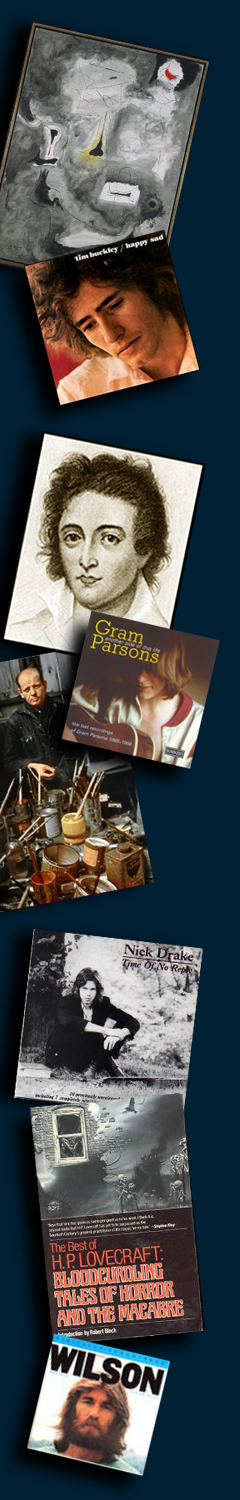

“Do you have anything from our lifetime?” I asked.

She pushed the door to her room closed to reveal some long-haired

guy with a beard staring sternly at me from the back of the

door. He looked like Charles Manson, but it said “Dennis Wilson”

above his head and “Pacific

Ocean Blue” under

that.

“Why do you have this here?” I said.

“It’s some old poster

of my dad’s. I like it -- he’s cute,” she replied. Everything

was old. She liked old things. She didn’t believe in reincarnation

or anything, but sometimes she felt that she might have been

born in the wrong time. She didn’t feel much connection with

the world, she felt connected only to things in the past.

That’s what she told me, but later.

Her bed was a girl’s bed, with a flowery comforter

and an old stuffed bear on the pillow. “It was my mother’s,”

she said. “Hold him, he’s soft.”

I was at a loss for words, so I just held on to

the bear and looked around again. There was a book on her

bed, Arshile Gorky: Paintings and Drawings. I put the bear

back on the bed and looked at the book. Stuck into the pages

was a large manila folder, and I opened the book to it. The

painting reproduced on the left-hand page was

a number of black patches connected with black lines on a

gray background.

Anna quickly took the book from me. “It’s a painting

about losing his earlier paintings and books in a fire,” she said, and put the book back on the bed.

“Gorky. It’s a funny name.”

“It’s not his real name,” she said. “He just invented

it.” |